Although once considered one of French West Africa’s most prosperous nations as it ranked third largest coffee producer and number one cocoa producer, Côte d’Ivoire faced issues with these export commodities contributing to its state decay.

In the 1980s, Côte d’Ivoire’s economy suffered from a fall in cocoa and coffee prices and a local drought during the 1983-1984 season caused severe cuts in the agricultural and hydroelectric output. Throughout this time, the industry GDP dropped 33%, services GDP down 9%, and agriculture GDP falling 12.2% (Mongabay.com).

Côte d’Ivoire is a West African country located along the Gulf of Guinea, bordering Liberia, Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Ghana. Its relatively small size (a little larger than New Mexico; about equal to Germany) has not stopped Ivoirians from largely affecting agricultural and economic sectors around the world. The country contains about 515 km of coastline, including the city and port of Abidjan.

Prior to gaining independence from France in 1960, Abidjan was the capital of Côte d’Ivoire. Soon after 1960, the capital changed to Yamoussoukro but Abidjan retained much authority, becoming the major shipping and financial center of French-speaking West Africa. Today, Abidjan is the largest city of Côte d’Ivoire and contains the second largest port in all of Africa (“Abidjan”).

So what does this have to do with agriculture, politics, or the rest of the world?

Following the 2010 presidential election, internationally-recognized President Alassane Ouattara banned cocoa exports from January until April. Supposedly, major cocoa companies indirectly supported the illegitimate regime of former-President Gbagbo with the means to purchase weapons and ammunition that had suppressed his opponents and launched a new civil war. By temporarily halting exports, Ouattara hoped to starve Gbagbo of the finances needed to maintain security forces and hold onto power, and eventually remove him from office. Although they had no way to officially enforce the ban, Ouattara expected to reach the public’s conscience by dissuading them from exporting in order to “starve Gbagbo of cocoa revenues.”

Societal consequence?

- African nations divide on how best to proceed:

- Nigeria: military intervention

- South Africa and Uganda: closer inspection of 2010 election

- ECOWAS asked the US, UK, and France to intervene but all deferred to the UN

- Widespread confusion as exporters and others in the Port of Abidjan decided whether or not to comply with the ban

- Many questioned future business relations with Côte d’Ivoire, especially Burkina Faso and Mali (landlocked neighbors whose business, transportation, and trade rely on the Port of Abidjan)

Agricultural and economic consequence?

- The price of cocoa jumped 15% in 6 weeks

- Impact of ban would’ve been more severe if not for the 2010 bumper harvest (surplus of cocoa on the global market), according to the ICCO

- Cocoa traders, chocolate makers, and consumers are forced to wait on effects to cocoa’s supply and price

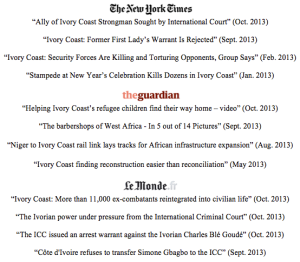

Much of the information presented here was gathered from these articles relating to the ban; its impact on the international cocoa trade; and what happened after the ban was lifted.